|

| Thad Jones wrote many of the tunes for this date |

Wednesday, June 29, 2016

Keepin' Up with the Jones Brothers, 1958

The Leonard Feather-produced album Keepin' Up with the Joneses, cut in 1958 for MGM, is one of the most obscure dates by a quartet that called itself The Jones Brothers. In reality, only three of the four participants (trumpeter Thad Jones, pianist Hank Jones, and drummer Elvin Jones) were brothers; bassist Eddie Jones simply shared their last name, yet the idea of billing the band as brothers probably was a gimmick that came from Feather himself, which would perhaps explain the scarcity of information about the identity of the quartet members on the cover of the LP. The choice of material also seems to be mandated in part by yet another inside joke: as the cover reads, the band is "playing the music of Thad Jones and Isham Jones." While it makes sense that the date would include compositions by Thad Jones, who plays flugelhorn here, the three tunes by Isham Jones, a prominent songwriter and bandleader of the 1920s and '30s, were most likely chosen because of his last name. Of course, like Eddie Jones, Isham wasn't related to the three Jones brothers, but whatever the reason behind the choice, the three selections written by him (all of them included on side B) are dependable standards that are among the highlights of the album, in particular "It Had to Be You," which features a lengthy piano solo by Hank. "On the Alamo" is taken at an agreeable, easy-swinging tempo and, again, is clearly dominated by Hank's piano before Thad even gets a chance to play his muted flugelhorn part. Another memorable moment is the closer, "There Is No Greater Love," which becomes the perfect vehicle for an intimate musical dialogue between Thad and Hank.

The rest of the tunes are all Thad Jones originals, and accordingly, Thad's flugelhorn is most often spotlighted, as in the album opener, "Nice and Nasty," a blues-tinged melody that lends itself easily to improvisation and even leaves some room for Eddie Jones to take a brief bass solo. "Keepin' Up with the Joneses" is based on a very catchy riff introduced by the trumpet and repeated by the piano. Both Thad and Hank have ample room to shine here, Hank showing his versatility by switching to organ halfway through the performance. "Three and One," whose title possibly makes reference to the fact that Eddie Jones isn't actually kin to the other three Jones boys, is a lovely mid-tempo number, and "Sput 'n' Jeff" features Thad's rather understated flugelhorn in contrast with Hank's quick, rippling piano runs. The brief dialogues between Elvin's unusually soft drumming and Eddie's noticeably quiet bass add freshness to the latter track. Though not always easy to locate, this forgotten session was reissued on CD back in 1999 and is particularly interesting and unique because the three Jones brothers didn't record together very often in the years following this date.

Labels:

Eddie Jones,

Elvin Jones,

Hank Jones,

Isham Jones,

Leonard Feather,

Thad Jones

Saturday, June 25, 2016

Benny Goodman Live on the West Coast, 1960

During my recent trip to Europe, I rediscovered an album that I'd long forgotten—the outstanding Benny Goodman Swings Again, perhaps one of the least discussed entries in the prolific Benny Goodman discography. Early in 1960, the King of Swing put together a swinging new band for touring purposes. The ten-piece outfit included magnificent musicians such as vibraphonist Red Norvo, tenorist Flip Phillips, altoist Jerry Dodgion, trombonist Murray McEachern, trumpeter Jack Sheldon, pianist Russ Freeman, guitarist Jimmy Wyble, bassist Red Wooten, and drummer John Markham. This was essentially an augmented lineup of the Norvo-led quintet that a few months before had accompanied Frank Sinatra at a concert in Melborne that Blue Note released in the '90s under the title of Frank Sinatra Live in Australia 1959. The Goodman album was released by Columbia and was recorded live at Ciro's in Hollywood and Harrah's in Lake Tahoe, which explains its subtitle, "Recorded Live on the West Coast." It features exciting new readings of Goodman classics such as "Air Mail Special," "Slipped Disc," "I Want to Be Happy," and "After You've Gone" and captures the fresh sound of this tightly knit band in a live setting, the updated arrangements leaving plenty of room for solos not only by the leader but also by Norvo, Phillips, Sheldon, and the rest of the sidemen, all of whom get several chances to showcase their talents.

Goodman is undeniably in top form and even vocalizes—and forgets the lyrics!—on "Gotta Be This or That," a number that he always enjoyed singing. The only ballad on the set list, Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's "Where or When," is actually one of the highlights, an opportunity for Goodman to show his tender side amid so much swinging uptempo material. Though the clarinetist's contempt for and dislike of vocalists was no secret, he features the lesser-known singer Maria Marshall on two selections, "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee" and "Bill Bailey Won't You Please Come Home," both of which she delivers in a style clearly reminiscent of Judy Garland. A rather obscure vocalist, Marshall also worked with the likes of Chubby Jackson and one Frank DuBois, though I admit the two numbers on this LP are the only recordings by her I've ever heard. Judging by the cover, one of the selling points of the album was a new nine-and-a-half-minute rendition of "Sing Sing Sing (With a Swing)," and although this 1960 arrangement is no match for the classic 1938 Carnegie Hall version, it's still an engaging, spirited performance. Critic Gene Knight, who attended one of these concerts, enthusiastically described Goodman's gig in the New York Journal-American as "an electric shock, administered musically . . . all the old favorites became new favorites again . . . there were shouts, cheers; customers stood up and applauded wildly . . . last night, as always, Benny was BIG!" And Benny Goodman Swings Again fortunately preserves on tape some of the excitement created by this early '60s Goodman outfit for our listening pleasure—alas, my sole complaint is that it only features nine tracks!

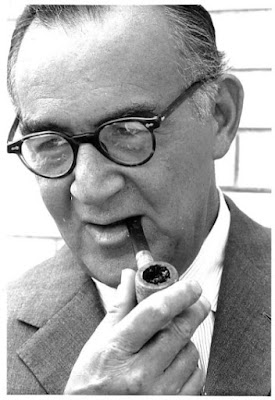

|

| Benny Goodman, 1960s (Photo: Herb Snitzer) |

Labels:

Benny Goodman,

Flip Phillips,

Jack Sheldon,

Jerry Dodgion,

Jimmy Wyble,

John Markham,

Live Jazz,

Maria Marshall,

Murray McEachern,

Red Norvo,

Red Wooten,

Russ Freeman

Thursday, June 23, 2016

The Jimmy Giuffre 3 on Atlantic, 1958

Back home in Tennessee after a three-week trip to Europe with my wife and three-year-old daughter, I resume the publication of Jazz Flashes with a post about Trav'lin' Light, a lovely album by the Jimmy Giuffre 3 with a most unusual lineup.

In 1999, Collectables Records reissued Jimmy Giuffre's 1958 album Trav'lin' Light as a two-fer with Mabel Mercer's aptly titled Merely Marvelous. Other than the fact that they were both issued on Atlantic and that they both feature a trio (La Mercer is actually accompanied by a trio led by pianist Jimmy Lyon), the reason for the pairing of these two records, as much as I like both of them, totally eludes me. Let's concentrate today on the Giuffre album, which is one of my favorites in his long and usually interesting discography. Giuffre, who was born in Dallas, TX, in 1921, is one of the most experimental and forward-looking musicians ever to grace the West Coast jazz scene, and despite his decision to become an educator, he continued making worthwhile albums into the '90s. Giuffre came up through the ranks of the swing bands, playing with Jimmy Dorsey, Buddy Rich, and Boyd Raeburn (quite the experimentalist himself), and he wrote Woody Herman's famous tune "Four Brothers," which lent its name to a whole saxophone section of the Herman band. In the 1950s, Giuffre, who could play tenor, baritone, and clarinet (as he does on Trav'lin' Light), emerged as one of the foremost proponents of the cool school, his music invariably characterized by its modern, experimental sound.

In 1956, Giuffre formed the Jimmy Giuffre 3 with Jim Hall on guitar and Ralph Peña on bass, but on Trav'lin' Light, only two years later, the lineup had become Giuffre, Hall, and Bob Brookmeyer on trombone, which led some critics to refer to the group as the new Jimmy Giuffre 3. By dispensing with part of the rhythm section and not using piano, bass, or drums, Giuffre lends the sound of this edition of his trio a sparse, minimalist quality that is unique on jazz albums of the period. In the original liner notes for the LP, critic Nat Hentoff refers to the trio's lineup as "intriguing, both in its present capacity to work tri-linear sorcery on the listener and in its indications for the future to other jazz players." Tri-linear sorcery—I can't think of a better, more poetic way of describing what Giuffre, Hall, and Brookmeyer are doing on the eight tracks included here. And there's little doubt that this album foreshadows Giuffre's interest in free jazz in the 1960s; though this isn't free jazz in any way, this record sounds very much ahead of its time, and the three participants are clearly striving to find new, exciting paths for their musical explorations.

On these sessions, Giuffre plays mostly clarinet, but he does switch to tenor saxophone on "Show Me the Way to Go Home" and to baritone on "The Swamp People" and "California Here I Come" (the latter, a tune not usually attempted on West Coast dates of the late 1950s), and he plays all three instruments on "Forty-Second Street." Half of the selections are standards, and Giuffre contributes four originals to the album—"The Swamp People," "The Green Country," "The Lonely Time," and "Pickin' 'Em Up and Layin' 'Em Down." Hentoff informs us that the first of these compositions "came into the book as a result of impressions from seeing some of the scenery and people while driving through the swamps," which shouldn't be surprising because most of the album, even the standards, has a definitely impressionistic feel about it. Just listen to the way the trio plays with the melody after briefly stating it on "Trav'lin' Light," for example. Even though this is quite an unusual context, there's a flawless musical understanding between the three men, who never fail to support one another throughout the album, and as a result, the chamber-music sound is very appealing. Upon its release, Billboard called this record "one of the best modern jazz LPs this year" (May 12, 1958) and I have to agree with the anonymous reviewer. I still don't understand why it's been paired with that Mabel Mercer album, though!

In 1999, Collectables Records reissued Jimmy Giuffre's 1958 album Trav'lin' Light as a two-fer with Mabel Mercer's aptly titled Merely Marvelous. Other than the fact that they were both issued on Atlantic and that they both feature a trio (La Mercer is actually accompanied by a trio led by pianist Jimmy Lyon), the reason for the pairing of these two records, as much as I like both of them, totally eludes me. Let's concentrate today on the Giuffre album, which is one of my favorites in his long and usually interesting discography. Giuffre, who was born in Dallas, TX, in 1921, is one of the most experimental and forward-looking musicians ever to grace the West Coast jazz scene, and despite his decision to become an educator, he continued making worthwhile albums into the '90s. Giuffre came up through the ranks of the swing bands, playing with Jimmy Dorsey, Buddy Rich, and Boyd Raeburn (quite the experimentalist himself), and he wrote Woody Herman's famous tune "Four Brothers," which lent its name to a whole saxophone section of the Herman band. In the 1950s, Giuffre, who could play tenor, baritone, and clarinet (as he does on Trav'lin' Light), emerged as one of the foremost proponents of the cool school, his music invariably characterized by its modern, experimental sound.

|

| Jimmy Giuffre |

|

| Jim Hall |

|

| Bob Brookmeyer |

Labels:

Bob Brookmeyer,

Jim Hall,

Jimmy Giuffre,

Mabel Mercer,

Nat Hentoff

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)